This writer was asked a seemingly simple but consequential question: “Is a Palestinian state actually possible — especially today, after the antisemitic terror attack in Australia?”

The response to this question too often centers on emotion, symbolism, or diplomatic slogans. Yet one principle remains clear: the establishment of a new country in a region plagued by conflict cannot succeed if its likely outcome is continued violence—attacks that spill far beyond the region itself.

This issue has returned forcefully to the center of public diplomacy and will fuel intense political debate following recent events. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., stated plainly that affirmatively declaring a Palestinian state without first achieving a definitive defeat of Hamas and securing clear Palestinian acceptance of Israel would only invite further attacks against Jews and Western values.

Meanwhile, at the recent Doha Forum, Qatari and Saudi officials renewed calls for immediate Palestinian statehood, effectively arguing that a war initiated by Hamas should now lead to rapid political recognition. Prominent American political figures participated in that forum, highlighting a growing divergence within Western discourse.

These differing perspectives reveal a deeper rift: one group sees grave risks in political gestures divorced from reality, while others—including Australia and several of America’s closest allies—continue pushing for immediate Palestinian statehood, sometimes with the explicit goal of pressuring Israel over civilian casualties in Gaza.

A serious approach must begin with reality. No Israeli government—left, center, or right—will accept a Palestinian state if it believes such a state could become a platform for rockets and terrorism. This concern is not unique to Israel; the international community also bears responsibility to ensure new states reduce conflict rather than amplify it.

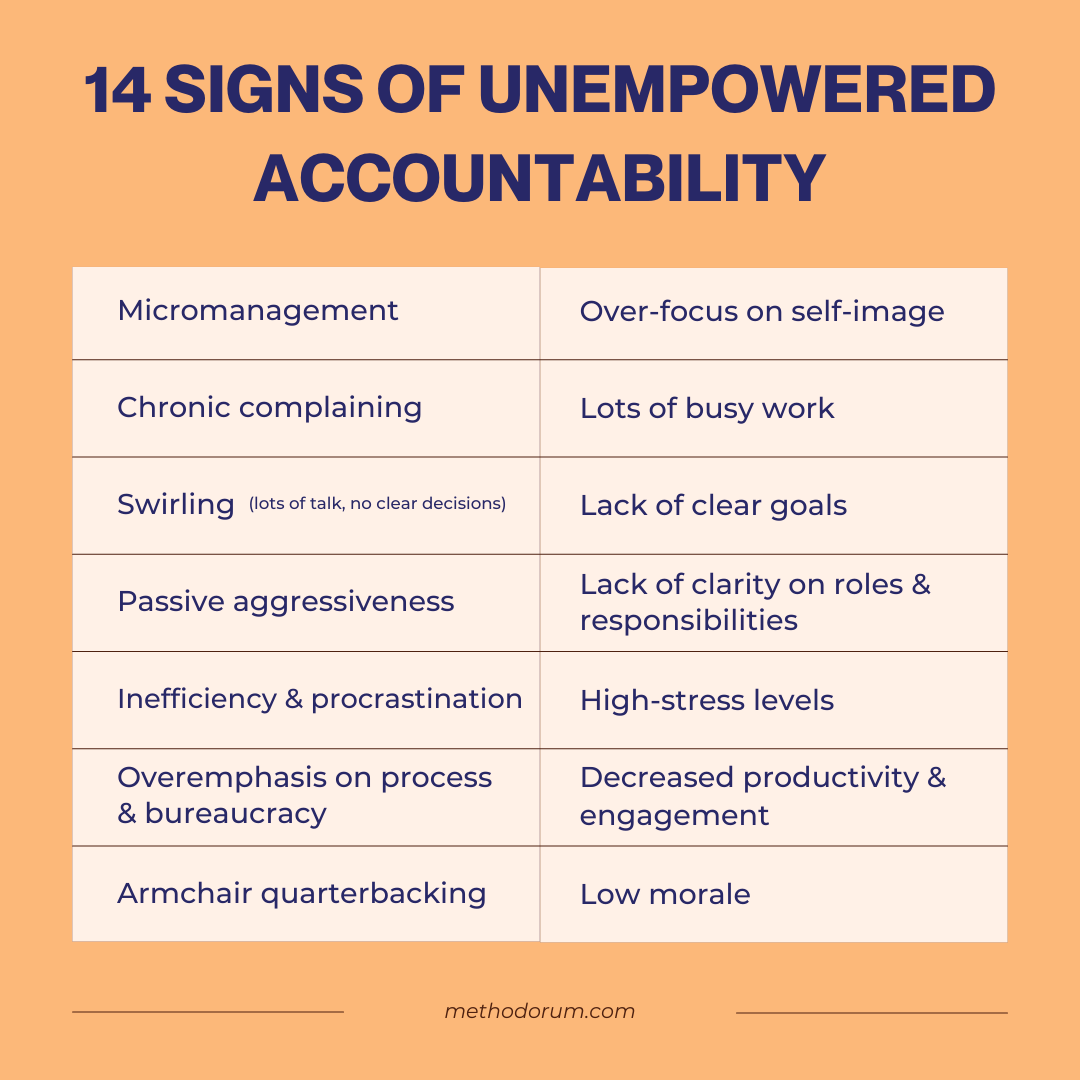

History offers no example of lasting peace built by ignoring security concerns of coexisting nations. Yet global discussions often treat statehood as if it were a diplomatic switch that can be flipped by declaration. A functioning state—capable of governance, providing security, and improving lives—cannot emerge through sentiment or symbolism.

A Palestinian state may be possible, but only if five difficult conditions are met. Without them, the discussion remains an illusion.

First, the Gaza war must end—and this conclusion must be recognized diplomatically. While we might not need a victory declaration, there must be acknowledgment that Israel has restored a baseline of deterrence and security, even as all sides mourn immense suffering and debate the conduct of the war. For decades, the region has drifted from truce to truce without resolution, allowing extremists to claim every conflict remains unresolved. After October 7, 2023, this ambiguity is no longer sustainable. A sense of finality is not a concession to Israel; it is a prerequisite for Palestinian political reconstruction.

Second, regional signatories must implement the ceasefire framework, while European allies must openly support it. The 20-point plan endorsed by Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE will only matter if these governments—individually and in coordination with the United States and Israel—actively enforce, fund, and administer it, particularly Hamas’s exclusion and disarmament. European nations, though not signatories, must align policies with this framework rather than retreat into strategic ambiguity.

Third, symbolic “recognitions” must give way to real state-building. Leaders such as Emmanuel Macron, Keir Starmer, Justin Trudeau, and Anthony Albanese have pursued symbolic recognition of a Palestinian state that does not yet exist and cannot function. These gestures serve two political purposes: expressing moral disapproval of Israel and satisfying domestic pressures. But symbolism does not build institutions, security forces, or economic systems. Recognition without foundations is not diplomacy; it is political theater—and it actively undermines future credibility.

Fourth, Palestinian leadership must accept that statehood is a process, not a proclamation. A Palestinian state cannot emerge from devastation without rebuilding infrastructure, reforming governance, establishing credible security institutions, and demonstrating the capacity to manage large-scale aid transparently. This requires a decisive break from past practices—including corruption, factionalism, and policies that rewarded violence. Statehood must be earned through governance and capability, not declared through slogans.

Fifth, the issue of the right of return must eventually be addressed with honesty. Millions of Palestinians believe deeply in a right to return to homes lost in 1948. Israel cannot accept an outcome that dissolves its demographic identity. While this may not be resolved immediately, no durable agreement can exist without confronting it directly and soberly.

Ultimately, a Palestinian state cannot be built in opposition to Israel’s fundamental security needs. Israel does not need to embrace every step of the process, but it must have confidence that the emerging state will not become a new platform for violence. That confidence will not come from symbolic declarations at the United Nations. It will come only from a disciplined framework in which Israel’s security is taken seriously, Palestinian aspirations are grounded in workable governance, and reality replaces illusion.

Only on this basis can a Palestinian state become not just imaginable but sustainable—and only then can the international community credibly confront the global spread of antisemitism.