Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has announced his most ambitious reform yet: a proposal to abolish the Senate and transform parliament into a unicameral, fully party-list chamber. This constitutional change, set to be voted on via referendum in 2027, marks a significant shift in the country’s political landscape.

The reform highlights an encouraging example of political evolution in a vast, strategically vital, and energy-rich nation bordering Russia and China. The U.S. has a vested interest in supporting Kazakhstan’s efforts to strengthen political stability and democratic institutions in this key Eurasian state.

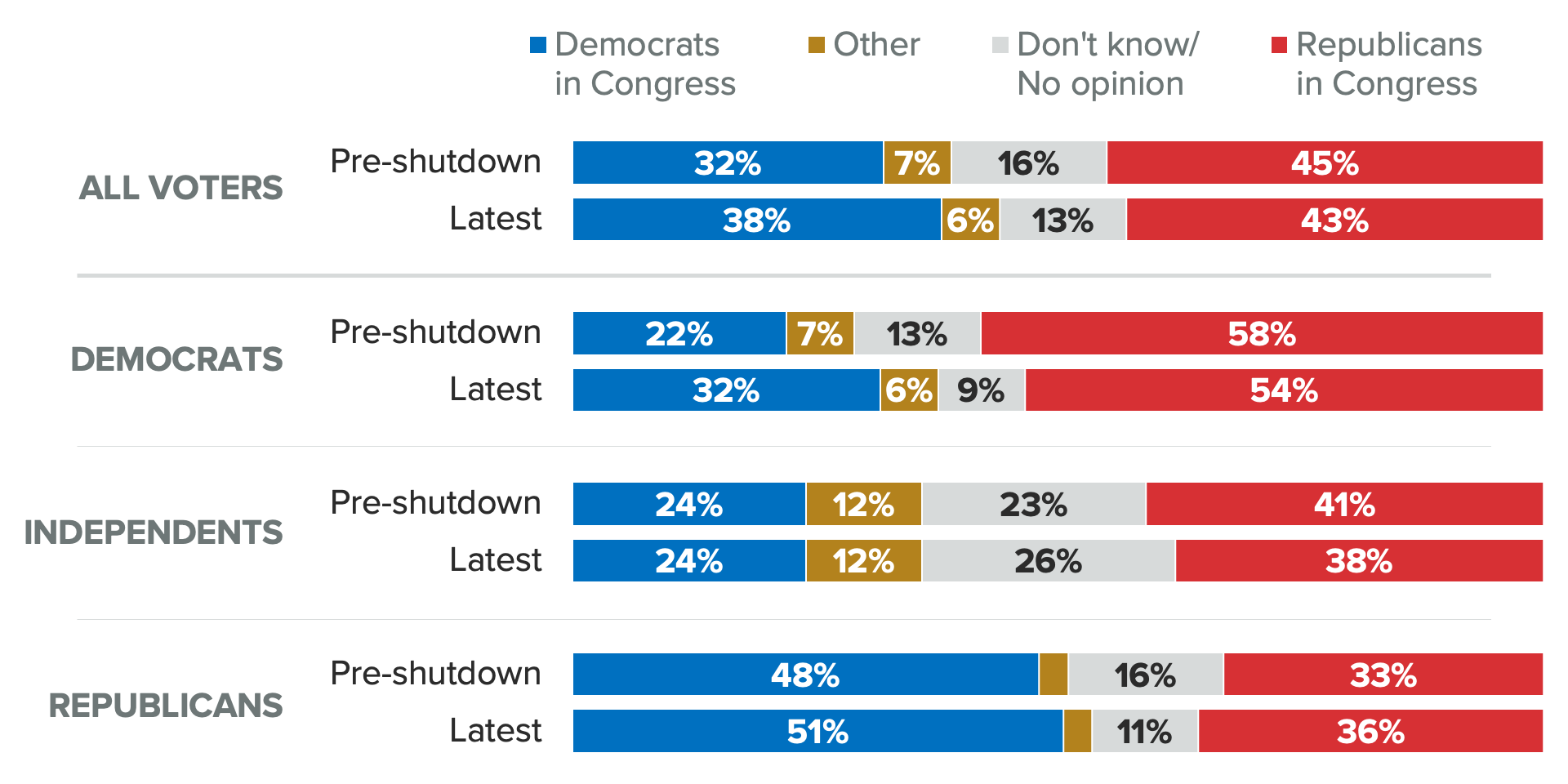

For decades, Kazakhstan’s Amanat party—first under the first president Nursultan Nazarbayev and now under Tokayev, though the latter is technically non-partisan—dominated politics with relative ease. In 2007, the party controlled all 98 seats in the Mäjilis, the lower house. By 2023, its representation had dwindled to 62 seats. Between 2007 and 2021, the ruling party consistently secured five to six million votes in four parliamentary elections. In 2023, it received just over 3.4 million votes—a decline reflecting the maturation of a multi-party system.

In the 2023 elections, Amanat performed better in single-member districts, winning 22 of 29 races (plus one allied independent), than in the party-list vote, where it secured 40 of 69 seats. Single-member districts are less predictable than the party-list system, indicating a growing political diversity. This shift suggests the president is willing to take risks to enhance democratic processes, even at the cost of his party’s short-term advantages.

The proposed reform would eliminate the Senate, an indirectly elected body where two senators per region are chosen by local assemblies and 15 more appointed directly by the president. Critics argue this structure reinforces central power, a dynamic the reforms aim to disrupt by amplifying voices from minority and disadvantaged groups at the national level.

Party-list parliaments, common in European political systems, can foster pluralism and coalition-building in stable democracies like Israel or Sweden but may hinder accountability in economically troubled or politically unstable nations. For Kazakhstan to benefit, it must simultaneously promote open media, genuine competition, independent courts, and avoid excessive state control. Civil society must also evolve alongside these reforms.

Encouragingly, Kazakhstan has already outpaced its neighbors, Russia and China, in GDP per capita, suggesting a material foundation for democracy. In 2025, Kazakhstan scored 63.8/100 in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, ranking 68th globally—a stark contrast to Russia (51.6, 135th) and China (49, 151st). The country also ranked 25th in the World Bank’s Doing Business index as early as 2019, outperforming Italy and Spain.

While political liberalization has lagged, economic openness and market reforms have delivered tangible improvements. This trajectory mirrors the “Asian Tigers” of the 1980s and 1990s, with Taiwan offering a close parallel. Like Taiwan’s semiconductor dominance, Kazakhstan controls about 40% of global uranium supply, a strategic asset that could elevate its geopolitical influence.

The next generation of Kazakh leaders may pair economic strength with a political model that ensures stability and trust, amplifying the nation’s growth on the global stage. By learning from historical precedents, Kazakhstan can balance sovereignty with institution-building, fostering long-term success. Supporting democratic transitions in the region aligns with broader interests in economic prosperity, trade, and investment.